Four Days in Bogota

Four Days in Bogota (All That Really Matters is that the Bill is Paid)

After some indecisiveness, I opted for a four-day spring break getaway, to Bogota, Colombia, traveling alone. This is not strange for me, as I’m drawn to and get around well in Spanish-speaking countries; and this is one for which I have particular affinity, having traveled around the country selling math and science books in Spanish translation many years before. I’m looking for interesting places in Spain and Latin America to spend time when I retire from the university in a couple of years, so I check out ones on my list as time and money permit. Bogota, despite its 9,000 foot elevation, currently ranks fairly high. The trip described in the following journal entries was interesting from the beginning, then got quite intense at the end. All I’ll say for now is be sure to take American Express with you when you travel. More on that later, but first let me tell you about the trip.

Friday 3-13

The lady cabbie couldn’t find my hotel following a 5 AM arrival in Bogota. It turned out to be a virtually unmarked residential building at the top of a very steep hill in the bohemian La Candelaria section of the city. Despite the early hour, the hotel is expecting me, and the night auditor buzzes open the iron gate and leads me down a dark stone hallway to a tiny room facing onto the central patio of the property, which is converted from a colonial era mansion. Immediately I begin to doubt its suitability to my modest needs, but I’m grateful to have a place to crash after the all night flight from Houston.

I sleep until 9:00, then go up to the front of the building to see what’s cooking for breakfast and order scrambled eggs. When the young lady innkeeper brings café con leche, I’m reminded that I need to order café tinto (“ink”) to get the strong black stuff I run on. Good scrambled eggs with ham come, and all is well. I defer on their offer of a guide for an all day tour of the Salt Cathedral, a long way out of town, saying I need some time to settle in and think about the possibilities, and for now I just want to walk around Bogota.

As soon as I get started, downhill toward the Plaza Bolivar, a vague sense of the implications of lodging at the top of such a steep hill at the 9,000 foot elevation of Bogota begin to dawn on me. But the morning is beautiful, there is much old and new to discover, and I’m walking, very cautiously, down the uneven cobblestones for a date with who knows what in downtown Bogota.

At the bottom of the hill lies the presidential palace and the grand Plaza Bolivar, the very center of Bogota, or, for that matter, of Colombia. But there’s a major public works project under construction on the near side of the plaza, maybe an urban rail line or something like that, and the expected grandeur of the site is compromised by trenches, barriers, and piles of earth. Ni modo, I’m thinking, no matter; I take a right along the Carrera Septima, past the national cathedral and the Museo de Oro, through the heart of downtown Bogota.

Adjacent to the Museo de Oro is an unusually fine marketplace of artesanias (folkloric souvenirs), and right away I make a modest start at dropping hard currency, just a refrigerator magnet and a handmade indigenous design t-shirt at first, but it’s easy (or so at this point it seems), and I’m already gaining momentum and beginning to think of maybe something a little bigger.

Next to the marketplace is an emerald store called El Palacio de la Esmeralda, just outside the Museo de Oro, where I stopped in to get a rough idea of the feasibility of an emerald purchase. Ouch, and yes, they are precious stones, indeed! A souvenir like that rates heirloom status in my world, and mad money won’t nearly cover it. But a fast-growing deep green seed has been planted.

Tiny unmounted stones here cost from $800 - $900 and spiral upwards, depending on size, clarity, and brilliance. Mounted on yellow or white gold, they go stratospheric from there.

Those prices in dollars, when translated into Colombian pesos, multiplied by 2,600 pesos per U.S. dollar (at that’s day pre-devaluation exchange), run into the millions of pesos. A venti coffee of the day at the new Starbucks costs about 5,000 pesos, which, I calculate, is a bargain compared to what you’d pay for it in the U.S. It has taken me a couple of days to gain a rough sense of what everyday items should cost, or how much cash I’m really carrying. The Bic pen and schoolboy notebook (with race car stickers!) I’m using to write this cost 2,800 pesos, or about a buck and a quarter. The $200, about 450,000 pesos, I changed at the airport has stretched impressively over the purchase of nice things, such as a fine leather satchel, t-shirts, books, etc. to take home, as well as meals, amenities, and a shoe shine on the plaza.

On my wandering rounds downtown, I’m looking for landmarks, like hotels where I used to stay when I traveled periodically to Bogota as sales manager for the Wadsworth International Group long ago. Dragging a bit from little sleep, I pounded along until I found the Hotel Tequendama, now a Crowne Plaza, which was the premier hotel of Bogota for decades. I had stayed there a couple of times back in the day. It looked inviting, and I was already beginning to ask myself why I wasn’t staying there again now.

I walked up and down Calle 19 looking for the Hotel Bacata, where I had stayed quite often in earlier times, but I couldn’t find it, though the neighborhood and sidewalk scene, with granite backdrop of a green Andean peak towering behind it, were familiar, even after all these years. As it turned out, the old hotel has been demolished and a 45-story skyscraper, the new Hotel Bacata, is rising to replace it. Its tall stairstep structure is already a striking sight on the skyline.

Along the way, I enjoyed the street scene unfolding along the long pedestrian stretch of Carrera Septima, where bands, artists, and assorted carnival-style entertainers were performing to attract multitudes of bogotanos passing by. In passing I noticed a playbill for a concert the next night at the Gaitan Municipal Theater by Chucho Valdez and his Afro Cuban Band. Although I was not at that point familiar with Valdez and his band and music, it looked like it would be a big and rocking show and an interesting way to spend a Saturday night, so I made a note to self to probably go.

Rocking on La Septima, Saturday morning

Near there I stopped for lunch at a place called La Florida, where I had a good tuna salad sandwich with a hot drink called an aromatico, an infusion of six local fruits and mints (e.g., strawberry, mango, yerba buena, maracuya), all mixed up, delicious and refreshing.

By this time I was beginning to feel the combination of altitude, short rest, and aimlessness, and I started moving back toward La Candelaria. Bogota is laid out on a grid, with numbered streets and avenues, which makes finding your way as easy as counting up and down numbered calles and carreras, much like in Manhattan.

I returned by a different route from the one which I had come, and the deviation brought me into an energetic section of La Candelaria. At around Calle 12 with Carrera 2, I came onto a small plaza, called the Plaza del Chorro de Quevedo, where there was a beehive of activity, with musicians playing both indigenous and electric instruments, groups of youth passing bottles, and artisans selling wares displayed on card tables or the cobblestones. The plaza was surrounded by coffee shops and bars, and there was a powerful buzz of peaceful energy circulating around. I would have liked to join in somehow if I had known how (maybe ask to see that guy’s classical guitar? No.). So I stopped for a few minutes, used the raised sidewalk for a bench, took a fat breath of thin air, then got up and passed on through.

Fatigued in mind and body, I was thinking about that steep hill and the effort necessary to scale it back to the hotel. Then there it rose before me, so near my room, but such an ordeal to conquer the height. Moving in my granny gear, very slowly, I angle up to the top of this Everest of la Candelaria, and finally make it up to my room at the top, where I step inside, take a deep breath, and collapse on the bed.

From my first glimpse of the room, I entertained doubts about the wisdom of choosing this out-of-the-way “boutique” hotel. But being a sturdy traveler, going solo, I figured luxury is optional and if the location is right, I can be quite satisfied with a cheap room if it at least has character and convenience going for it. The climb winded me physically and mentally, and the thought that I would have to climb it again at the end of every trip out of the hotel clouded my plans like a monsoon; but the room was prepaid and I still had no thought of moving on from there.

That is, up until I went to take a shower in the postage stamp bathroom and couldn’t get water hot enough to take a comfortable shower. I tried to imagine taking one with the water as freezing as it was, but couldn’t do it. It warmed up a little bit after five minutes, but not nearly enough to be called lukewarm. I tried for a minute to think of how I could make this unhygenic situation work for four days, but I couldn’t do that either, so I decided I had better make a different arrangement for the next day.

After resting a couple of hours, I set off on another long walk, back in the same direction I had gone earlier, toward the Hotel Tequendama. Nothing will make you spring for luxury like having no hot water in your cheap hotel room! On the way I stopped at an Italian restaurant called La Romana on la Septima and had some slightly overcooked salmon with a Ruffino sangiovese.

A short walk further on I completed my mission when an eager young chap at the Tequendama registration desk (later to become known to me as Johnny) enthusiastically took my reservation for the next night, and I made the long walk back to La Candelaria with the satisfaction of knowing that tomorrow I could shower to my heart’s content there in the lap of luxury.

That little plaza (del Chorro de Quevedo) in La Candelaria was really happening now in the evening, with a rock band dressed as clowns playing rhythm and riffs behind a young lady with a bulbous plastic nose who was shimmying inside of four hula hoops that she made go up and down her torso while doing the hand jive and mugging for the crowd. I kind of hated to leave because that place was really alive, but I hated to leave even more because the next part of the walk was the brutal Andean climb of the last two blocks back to the hotel.

Ever so slowly, needles in my legs and heart pounding like a bass drum, I made it back – but this time with the satisfaction of knowing that I could take a cab out of there in the morning and be done with the rough climb home. After an uncomfortable hour of leg twitches, everything loosened up, and I slept like the dead, burrowed in and blissed out, until the morning sun was well up.

Saturday 3-14

After remembering where I was and clearing my head, I decided to make a clean early getaway, though I realized the conversation at the front desk could be awkward. With an apologetic nod, I told the woman the accommodations were not meeting my needs, and I had decided to go to the Tequendama. The contrast of that brand name with this place short-circuited the need to recite specifics (e.g., cold water, steep hill). The young woman handed me a customer satisfaction questionnaire and requested that I fill it out, but I politely declined. Then she charged me 2,000 pesos for the bottle of water I had used for tooth brushing, which left a bad taste in my mouth. I asked them to call me a cab, but as soon as I hit the sidewalk one approached, and I was off to the Hotel Tequendama.

A potential fly in the ointment was that it was 7:30 AM, and I expected to have to check my bags for a long wait before checking in, but fate was smiling kindly, and up the oak-paneled elevator I rode. My room, on a corner of the twelfth floor, had a 150 degree view over the upscale northern sweep of la Septima to the majestic mountain rising just behind. The hot shower was like decadent pleasure, and any and all tension was substantially released. The hotel exceeded in luxury what I remembered, and I reveled in it like a dog in summer grass. Complimentary breakfast buffet, omelet bar, assortments of fruits I couldn’t name, genteel service, general happiness. Credit card, some cash, and a debit card – do what I want to, no need to skimp; life is very good.

After cleaning up and settling in, I set out on foot toward the Botero Museum, near La Candelaria and the Plaza Bolivar. It is in a complex of museums underwritten by the Banco de la Republica (Art Museum, Numismatic Museum, Garcia Marquez Library). In the museum, in addition to dozens, if not hundreds, of works by the great Colombian artist Fernando Botero, there are salons full of others by Picasso, Matisse, Lautrec, Leger, Klimt, and many others, out of Botero’s personal collection and given to the Museum upon its establishment.

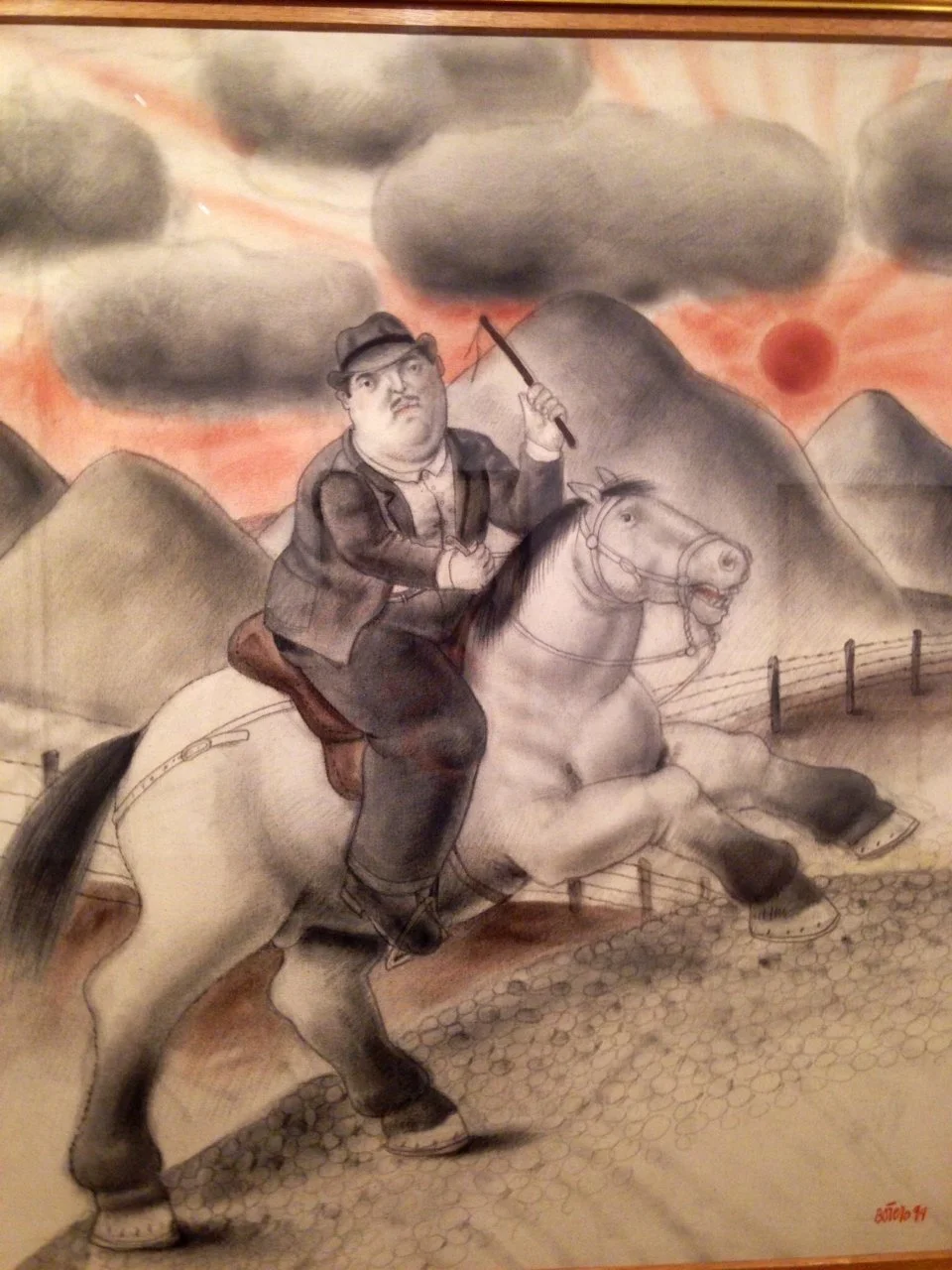

Botero’s works mostly feature rotund, identifiably Hispanic people in very artistic caricature, in situations ranging from the mundane to the surreal, and in many in which the mundane meets and coexists peacefully with the surreal; a big family posing with blank expressions, a smiling skeleton of death playing wicked guitar, a man in suit and tie raring back on a stallion beneath Andean peaks, Adam and Eve reclining, sharing lazy bites of apple in a luxuriant garden. Through juxtaposition of the mundane and fantastic, he reels in a vast spectrum of mind and experience with elegantly concise imagination. He’s like Muhammad Ali as an artist, playing rope a dope with you before throwing the right hook realization that truth and beauty are alternating harmonies, like emeralds and gold. He’s every bit as clever and much deeper than you first suspect.

Across the street, next to the Garcia Marquez Library, is the huge glass front bookstore of the Fondo de Cultura Economica, a publisher and bookseller based in Mexico. I searched the extensive Colombian literature section and was impressed to find the whole catalog of works written by friend (what’s the right word?) Macky’s father, Jose Antonio Osorio Lizarazo, who died in 1964 and whose writings from the first half of the 20th century are enjoying a fresh airing and resurgence in Colombia.

Macky (Maria Cristina) and I share a close bond of some kind, though, despite multiple earnest tries, we have not been able to sustain romance for more than a few months at a time. She’s public relations director for a major corporation with responsibility for all of Latin America. I think she can probably do that job better than any person living, but still she talks about retiring sometime soon. Personally, I have a hard time seeing that because she needs to be out and about. She has three citizenships (U.S. and Venezuela besides Colombia), but Bogota is her native and perhaps most permanent home (at least after Houston, we’ll see).

Her father was a self-taught journalist who became a successful novelist and political writer. From humble origin with little benefit of formal education, he became an important figure in the literary, intellectual, and political life of his country, so much so that eight or ten of his book titles have been republished recently. When she was little, Macky was his princess, and he spoiled her so much that she’s stilled spoiled today. In the store, I bought a couple of books by Latin authors but none by Osorio, because Macky had already given them to me one time on her return from Colombia.

After a long stroll through La Candelaria and the government complex, I ended up back at the Museo de Oro, which I thought of more or less as a tourist obligation – lots of dazzlingly shiny little artifacts of ancient Andean peoples. But I found it curiously unmoving. The descriptions focused on technical aspects of the mining and fabrication of materials exhibited and little on what to me is the more interesting ethnohistorical significance of the pieces. But one sociological note did catch my attention: that the miners and artisans were highly regarded for their practical and even mystical knowledge of secrets of the earth, as revealed in locating, extracting, purifying, and creating beautiful and powerful things with precious stones and metal. This implied to me that those who would understand earth’s inner secrets would do well to study pre-Columbian earth science. And maybe Baron von Humboldt, who knew it all so well.

Virtually next door to the Museo de Oro is the Emerald Museum. From my store visit the day before, emeralds had captured my attention and imagination. I thought I would see what I could learn at the museum before exploring stones in their natural glass retail display case environment. Attendants at the museum greet you at the ground floor entrance and take you in an elevator up to where another guide leads you with a breezy patter all about mining – geography, lore, and technique – through large dioramas of mine shafts with ore veins, explaining how and from where the precious stones are extracted. Through this you can come to appreciate the great transformation from some dark matrix beneath mountainous earth to the stone of lights you can almost feel flashing from your ring finger.

This is a private museum, designed by a good marketer. The tour ends at a boutique with open doors to where fine stones in elegant settings can be bought. I was interested, like a poor man in a beauty queen, and asked the guide in a discrete aside about the prices here, to which he confided that they were “somewhat elevated,” but quality was assured.

Meanwhile, my little weak spot of sensitivity for green fire set on gold became a broken out rash. And, as luck would have it, the museum exit is only steps from the entrance to the store where I had stopped to browse the day before. Dangerous as I knew this to be, I stepped right in.

The same woman who had attended me the day before did so again, with the familiarity of cat to a mouse that’s come back for the cheese. For starters, I asked for an explanation of the great variation in value of the stones on display. At first sight they look more or less equivalently green to the uninitiated, but with just a little bit of observation and instruction, highlights (good) and impurities (bad) become evident. I started asking to see oval stones, ones large enough to flash some, but not be conspicuously conspicuous, but just a little bit so.

A long discussion followed, but it focused in quickly on a stone that admirably satisfied these requirements. Then we searched the store and our collective imaginations for the right setting. This was nuts because if we found it, they would still have to mount the stone before my late Monday departure. But of course I proceeded anyway.

After much ado of looking at, sketching, and rejecting settings, and a few repetitions of “kind of like this, but…,”, we found one that would make what we pictured as a handsome ride for the stone, and I pulled out old faithful (Chase credit card) and had the thin guy in the suit who was standing there hit it hard for half the purchase price, the rest to be paid when the ring is ready on Monday.

Of course it was to be expected that on the first pass the Chase fraud alert line rejected the transaction. This was despite the fact I had received a letter from Chase a couple of months before telling me that I would no longer need to call beforehand to let them know when and where I was traveling. But no problem, right away I received an email querying me as to whether I recognized this transaction. Yes, I do; okay then, try it again; charge approved. Good faith and international goodwill reigned, and we could wrap it up on Monday.

Chucho Valdez and His Afro Cuban Messengers

After dinner at the hotel, I walked to the Chucho Valdez concert; I had stopped at the theater box office for a ticket while passing by that afternoon. The theater was very large and impressive, maybe 2,500 seats, probably from the twenties or thirties, with an interior update of recent vintage and excellent sound and acoustics. The crowd was mostly older and upscale, with some youngsters sprinkled around. You could feel excitement in the air.

Being Cuban, Valdez is not well known in the U.S., but is a giant throughout Latin America and in jazz circles everywhere. His Afro Cuban Messengers consist of a drummer, two other percussionists, a trumpeter, and a bassist – virtuosos all. Valdez himself is a genial, hulking, seventyish figure wearing a backward baseball cap, seated behind a grand piano, the ultimate potential of which he is about to exploit for the capacity crowd. The band was blazing with chromatic virtuosity from each member in solos and playing off of each other in a synergistic mix that lifted the crowd to ecstatic heights, then swept it away with irresistible artistry and power.

Halfway through the 100 minute set, the big man’s wife, Mayra Caridad Valdez, about the same age as he, ambled out slowly from backstage to sing a few standards. She brought the house down completely with her first number, “Una alma como la mia,” sung with deep searing soul and passion, fronting what had suddenly become just about the best back-up band in jazz, and she received a standing O right there in the middle of the set. She sang three more strong numbers, including “Besame mucho,” before retiring again backstage to let the band pull out all the instrumental stops again.

During the encore number, after another sustained standing ovation, the slimmer of the two percussionists started dancing wildly, with the most athletic and rhythmic gyrations, and continued doing so all around the stage and then into the audience and finally back to his place in the band. Chucho then made a mocking feint to start doing the same with all the momentum of his shaking girth, but he quickly turned and signaled to the band to take a final bow, and the curtain came down on an epic show. I left the hall and walked back to the hotel a more enlightened gringo, for having experienced the beauty and power of Chucho Valdez and the Afro Cuban Messengers.

Sunday 3-15

I wandered out of the hotel before breakfast to try to find a cup of coffee to sit with to meditate for a little while before breakfast. Vendors in a flea market near the hotel were setting up booths in a vacant lot, and a multitude of cyclists were wheeling north along la Septima, which is closed to auto traffic. I asked a gentleman in the doorway of a small restaurant for a cup of tinto to go and found a bench in a small plaza to savor it.

Many people were out in groups with dogs, kids, and grandmas. The dogs made me miss old Blakey, departed friend of friends. Meditation turned to the spiritual qualities and life lessons an animal like him can teach you: faith, love, constancy, and perseverance. I realized I’m caught between conflicting loves and desires: i.e., travel and having a dog. They’re just not compatible if you live alone and travel much. So for the foreseeable future, I’m holding dear old Blakey’s memory and keeping my passport handy.

After returning to the hotel for breakfast and shower, I set out again, northward up la Septima, which was alive with pedestrian traffic, shouting street vendors, kids playing with soccer balls and roller skates, lovers laughing and caressing, and beggars with hands out grimacing.

Just as I started looking for a comfortable place to sit and write, I discovered an enormous, beautiful park that, though it was also alive with people enjoying Sunday leisure, still had plenty of empty benches available. The one where I sat down was next to a dugout roller rink where little kids were circling like demons at warp speed, while some adults struggled painfully step by awkward step to stay on their tender feet.

After writing for a while on a bench with an arched back, I needed to get up to straighten my back, and wandered back toward la Septima, where a large gathering was jazzercising to the direction of a leader who was kicking and dancing on a stage large enough for the Rolling Stones and their whole musical retinue. When I passed by going the other way just an hour later, the stage had been broken down and carted away, and the crowd dispersed.

I found another bench with straighter back and sat down to continue writing. I had barely begun when an elderly gentleman approached, stopped, and said “you moved” with a bit of a twinkle in his eye. “Yes,” I answered, “I just needed to straighten up my back.” He sat down uninvited, introducing himself as a professor of medicine at the Universidad Javeriana. We had a very pleasant conversation, about travels, changes in Bogota over the last thirty years, and the rent of a small apartment in this nice part of town. According to this gentleman, a small apartment in that area would cost around $600-700 per month. (Later, walking back to the hotel, I stopped in at the sales office of a high rise condominium building going up right near there, and they showed me a small but nice one bedroom priced at $91,000 at the current exchange rate.)

That conversation with the doctor might have gone on a good while longer, but I excused myself to move on northward along la Septima. It was only a few blocks to the National Museum. Entrance there was free, but you had to show your ticket and have it punched to enter any salon. I suppose they might kick you out if you didn’t have one.

The featured exhibit was a collaboration between Mexican and Colombian national art councils. The pieces were of mixed quality and mostly Mexican. There were beautiful desert and mountain landscapes, several portraits (of society women and indigenous girls) by Diego Rivera, and modernist works by Tamayo, Siqueiros, and Orozco, among many others, all very much to my taste. The rest of the museum appeared to feature pre-Columbian culture and artifacts that, at least at that moment, did not much interest me.

Indigenous girl, by Diego Rivera

I sat and wrote for a while in a beautiful courtyard garden in the center of the building. My hat, which I always wear when out in sun, drizzle, or thin Andean air, seems to draw curiosity, so when a guard came out to rest his legs on a break, he asked where I was from, thinking it must be Australia, because of the hat. Another stranger I spoke with later pretty much insisted I must be from Canada, not the U.S., for the same reason. I gave the guard a brief introduction to Houston’s cultural and geographic significance, which, after a brief spark of interest, reminded him it was time to get back to punching those free tickets.

Author with hat

About this time, I felt the miles of high altitude wandering catching up with me and returned to the hotel to rest and relax the rest of the day, venturing out only for a quick return to La Florida for a steak sandwich and another aromatico before turning in early. Tomorrow would be the trip’s interesting conclusion.

Monday 3-16

My plan for the last day in Bogota was simply to walk, to the far reaches of La Candelaria and wherever, to take in sights that might stay with me and tire myself out so I could sleep on the red-eye flight back to Houston, scheduled for midnight departure. I had a 4 PM appointment at the jewelry store to pick up the ring and pay the balance. I was a bit apprehensive about how that might work out. The latter part of the day turned out to be more than I had bargained for.

I began the day with a little walk out of the hotel to get a cup of coffee and sit in the beautiful garden nearby that I had discovered the day before. But, after accidentally finding the new Starbucks and buying a venti café tinto, I discovered I couldn’t reach the elevated garden from the route I had taken and sat down on a bench in front of an office building where the well-dressed day shift was arriving for work in significant numbers.

I headed from there into the heart of downtown without much fixed purpose other than to keep my eyes open for anything interesting to put in my file of mental impressions and photos to take back home. I stopped in at the jewelry store to tell them I would drop by for the ring at four instead of waiting at the hotel for delivery.

Wandering out of there, I sat on a bench in the large plaza outside, in front of the Museo de Oro, to write for a while. When I was well into it, a young Brazilian girl, of maybe 20 or 21 years, sat down on the bench next to me. She was carrying an introductory Portuguese textbook and spoke in what I would call Spaniguese. She was casually but decently dressed and showed no outward signs of distress. She told me she taught Portuguese lessons but business wasn’t good and she was hungry, so could I help her. It was 10 AM. I really didn’t want to take out my wallet and give her money, as I didn’t have much, eyes in the plaza would certainly be watching, and nobody wants to feel like an all-comers ATM. But she was nice and might also have been really hungry. Having enjoyed an omelette before leaving the hotel, I wasn’t quite ready to eat anything myself, but I told her I would be happy to meet her for lunch in a couple of hours if she could hold out. She began to protest and just about started begging for money now, when I just said, more or less (allowing for translation), that’s my offer, take it or leave it. She left and I resumed writing.

From there, maybe a mile away in La Candelaria, I was delighted to unexpectedly find that the Bank of the Republic’s museums were open on Monday. The art museum was excellent and very interesting, with mostly Latin American works from colonial to contemporary times. I took a lot of pictures. Much of the work on display and the museum itself made excellent impressions on me.

Guitar player on the plaza

From there, after walking quite a while to the far edge of La Candelaria and then back through the Plaza del Chorro de Quevedo, where a few people were sitting and one bearded young man was playing flamenco on classical guitar, I ended up back downtown, inside the Lerner bookstore, the premier bookstore of Bogota. It’s a very comfortable place to sit and read, and one could do so all day long without anyone batting an eye. I again found Macky’s father’s reprinted books on sale. I picked up a few books to buy but was surprised and disappointed that the card reader at the register wouldn’t take my credit card. It wouldn’t take my debit card either, and I wasn’t carrying enough cash at that time to do it that way. The credit and debit card situation was inexplicable, but it was just about time to go to the jewelry store to complete the ring purchase, and my confidence about being able to do that quickly and easily was in free fall.

It’s rainy season in Colombia; a monsoon often comes through with a brief afternoon shower and then moves on in an hour or less. This day it was an aguacero, hard and driving. It left an inch in an hour while I was reading in the bookstore, and it had just subsided when I splashed over to the jewelry store, trying unsuccessfully to spare my walking shoes.

The ring, which an ensemble group of employees unveiled with every flourish but a drum roll, is a dazzler – a fair-sized deep dark stone with subtle lights around the edges of an unfathomable center, set on smooth and handsome yellow gold. Splashy yet reserved, muy soberbio. My only concern at this time, after the bookstore incident, was being able to pay the balance (3,180,000 Colombian pesos).

The answer quickly turned out to be the expected no, just as I feared. Unlike on Saturday, when a quick click on a fraud alert email overrode the block, this time we couldn’t do it. So we (several women and the one man and I) ended up spending a very long time on the phone with the Chase fraud alert line in the U.S. trying to resolve the problem. The service rep assured the store personnel that it was not a credit problem, and repeatedly told us to try it again now that the block had been released, but this was to absolutely no avail. We thought it might be the card reader and tried another. Didn’t work. We even ended up taking a taxi across town to another location of Palacio de la Esmeralda, adjacent to the Tequendama, to try it there, but it wouldn’t work there either. At that point, I went inside the hotel to ask if I could get a cash advance on the credit card from them. The manager unhesitatingly said no. (That was when I first started thinking about my situation at the hotel.)

In all, we tried by all possible means to get the card to work from 4 PM until 7 PM, at which time we gave up in frustration and exhaustion, and I went into the hotel to pack and get some dinner. I was really wasted from the experience and becoming vaguely concerned about the hotel. I say “vaguely concerned” because the manager suggested in my earlier conversation with him that the hotel had its ways of getting a little job like this done, and of course I believed that immediately.

Besides me, there was only one couple in the hotel’s huge dining room, but a saxophone player blew bravely on through his muzak repertoire. I barely had the strength to eat and not much appetite either, but I choked down an overcooked chicken breast to avoid hunger pangs later on the flight. The moment of truth was approaching, but I was too done in to think or care much about it. Even then, it didn’t seriously occur to me that anything was or would likely be much out of the ordinary.

The friendly, enthusiastic young man who attended me at the reception desk, the same one who had made a reservation for me days earlier, identified himself a bit later as Johnny. He started explaining the itemized bill to me line by line, but as wasted as I was, I just asked him to show me the total, which was $584 (1,075,607 pesos). (Not going over it line by line ended up costing me quite a bit in mistaken phone charges, but in light of what follows, that was trivial.)

Immediately the card didn’t work, and an ordeal began. Johnny (Juan Sanchez) disappeared backstage with the card, to try another sure-fire method from the hotel’s bag of tricks, he said, and was gone for 15 – 20 minutes. 50 – 50 chance that this might work, I thought.

Back comes Johnny, with shoulders slumping, seemingly thinking that he’s whooped. It’s about 9 PM, and I have a flight home to Houston at midnight. I have a little over $50 cash in my wallet, no credit card that works, my debit card has also been deactivated, and here we go again, on the phone with the Chase fraud alert line. The hotel manager is aware of the situation and joins us in the little council.

After several attempts, we finally get a Chase supervisor who appreciates the gravity of the situation. But repeated frustration proves there’s nothing she can practically do. She has told the hotel my credit is good and even given them an approval code for the charge, but they can’t use it because it requires mediation of the hotel’s bank, which lacks an after-hours service line. At least that’s what we think is holding us up. The manager apparently remains skeptical about my credit-worthiness for the charge, despite the bank’s assurance and the approval code they’ve given him. It gradually becomes apparent that, despite my increasingly urgent need to leave for the airport, he won’t let me go until the bill is paid; and there is simply no way to pay the bill.

After I flamed out in frustration, Johnny took the lead in speaking with the Chase supervisor on the phone. I have to say that, despite the fact that we didn’t make any practical progress, he was magnificent. His accented English was quite good, down to fluent use of “pissed off” with understated savoir faire. Out of empathy with my situation, he had become quite emotional, and he was thinking, correctly, that it would be considerably cheaper to get me out of the hotel and onto my flight than to have me miss it over this conundrum. When toward the end of the conversation he passed the phone back to me, I found that his breaking voice pleading with the Chase supervisor had affected her too, but there was just nothing more that she could do. None of us knew what kind of block we were working against, but it was clear that my credit and debit cards were out of business and down for the count. They were all the access I had to my ample cash and credit balances back in the U.S.

As 10:30 approached, we’ve been locked in this (what was to me) hellish situation for an hour and a half, not to mention the three hours earlier at the jewelry store, and I needed to either go to the airport now or come up with a Plan B that so far has not presented itself. I suggested a review of the situation to the assembled hotel personnel, manager in the center.

“You know it’s not a credit problem; in fact, you already have an approval code, and it’s urgent that I leave.” “No, sorry, we haven’t been paid.” The manager, aware of my attempted ring purchase, asks if I have something I can leave as security. (The scumbag, I think, wants the ring.) Books, t-shirts, leather satchel, that’s about it. The whole thing seems like a cruel joke or nightmarish twist of fate, possibly devised by the devil or some other metaphysical force or entity. Did the ring open a cosmic force field? Or just expose an unexpected snare in the international payments system? Or all of the above? It almost seemed funny for a second, but neither the time nor perspective was quite right for a laugh. It struck me that at some time or another a simple situation like this, paying a hotel bill with a perfectly good credit card, will just have to go to an extreme length of difficulty that you couldn’t possibly imagine, just because the alignment of the universe has a slight wrinkle in it somewhere.

I asked the manager what they would do with me, put me out on the street like the vagrant they seemed to think I was? And I suggested that the problem could easily end up costing a good bit more in the end than the $584 that we couldn’t get put on the card.

The only conceivable Plan B that occurred to me was to contact the U.S. Embassy in Bogota. I was trying to find the number on my cell phone when Johnny called me over and said, “Mr. Brown, I will put this charge against my salary so you can go. Just go to your bank tomorrow and send money.”

I was really touched, so much so that I thought I can’t really let him go to that length for me on this. Plus by that time, I kind of wanted to take the case to the embassy. But even as I said that, I was heading for my bags. Grabbing them and starting for the door, I turned back and stood face to face with the manager and said, “it doesn’t take much to destroy faith and confidence, and all of this over $584 dollars…is just not right” and turned and left in a hurry.

I told the cab driver I had prepaid the fare (which was included on my unpaid hotel bill), and he dropped me off at the airport. Seven hours later, I was heading toward the house in morning rush hour traffic down US 59 in Houston. My credit card worked fine to pay my airport parking.

Checking my bank accounts the next morning, I found the $584 charge on my credit card statement, but strangely there was no name (of the hotel) posted with the charge, only the amount. But I took it to mean that the hotel had run the charge with the approval code they had been given and that it had gone through. Why else would it show up on my statement? With that thought I relaxed about the hotel situation and thought about what I wanted to do about the ring.

Ten or twelve hours of oblivious sleep can wreak recuperative wonders. I figured out how to dial Colombia from my cell phone and called the jewelry store. I arranged for them to email me information that would allow me to send the balance I owed on the ring online. We clung to that prospect for a few hours before giving up on it. Then we tried, with the help of my local Chase branch manager, the lovely, keen, and helpful Danielle, to wire it to them. Well, why wouldn’t that work? I didn’t know then, but it just didn’t.

Finally, the next morning (Thursday, three days after my return to Houston), the owner of the jewelry store suggested by phone that we use her Paypal account. I told her I didn’t have an account, but she said that’s not necessary. Actually, I did need to open an account to be able to pay a peso account in dollars, so I did, and that was that.

Talk about a relief. I could hardly believe it when I saw proof of the transaction. So then there was just the matter of getting the little ringy dingy up here. By this time, I had had a lot of phone conversations with Marcela, the owner of Palacio de la Esmeralda, and I was pretty sure she was going to take care of that quickly and effectively, as she certainly did. It arrived exactly one week after the appointment to pick it up at the store. I believe it may have arcane significance and powers, but whether for good or evil I’m not sure. I’m looking for a more rational explanation of these strange events.

I was then relaxing, thinking the hotel bill also paid. But such was not actually the case. The next time I checked my credit card bill online, the $584 charge had disappeared. That struck a little cord of “oh shit, they must still think I stiffed them.” So I called the hotel and asked for Johnny. Well, the girl who answered said she didn’t know anybody there by that name. No, Juan Sanchez, No. One of us hung up on the other, but I can’t remember which.

Moments later my phone rang showing a number from Virginia, but it was really Johnny calling from Bogota. Here we go again to the inexplicable extreme of futility to pay the goddamn hotel bill. I don’t remember how many conversations we had over it this time, but I took it directly to Danielle at my local Chase branch, and we tried to put it on my debit card. We photocopied the card front and back and sent it by email. Within the hour, I noticed on my checking account activity a charge from the Hotel Tequendama for $411. This was joy and puzzle both; they got their money, but that’s much less than what I thought the bill was. Johnny called me just a little later, and in a very happy and relieved conversation, he confirmed that the debt was satisfied and explained that the peso had been devalued, by quite a bit. But all that really matters is that the bill is paid.